Was The Happening the disaster everyone remembers? Or was it just fatally misunderstood? One man makes a case for the latter…

Was The Happening the disaster everyone remembers? Or was it just fatally misunderstood? One man makes a case for the latter…

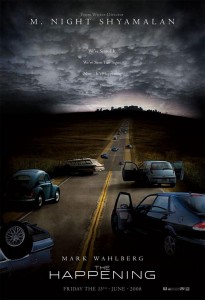

Looking back at M Night Shyamalan’s The Happening

by Craig Lines

For a while there, M Night Shyamalan was Hollywood’s golden child. A modern-day auteur who blurred the lines between populist and arty, cult and mainstream, genre and straight drama to great acclaim. Yet now, almost everything published about him talks of his critical fall from grace. It’s like parts of the industry see him as an embarrassing uncle at a wedding who’s still invited out of courtesy but is inevitably going to make a fool out of himself if you let him near the camera…

Sure, there’s an argument to be made that Shyamalan has had a couple of misfires but when people start referring to “embarrassing flops like The Happening” I have to draw a line. I personally consider The Happening as one of the best Hollywood movies of the last decade and, by some distance, the most misunderstood. It is, without question, Shyamalan’s masterpiece. So I’m setting the record straight.

If you’ve not seen it, Mark Wahlberg stars as Elliott Moore, a science teacher who must make his way safely across Pennsylvania when a suspected terrorist attack causes people to commit suicide en masse. The radio suggests it’s an airbourne toxin. Shelter from it appears nigh on impossible. Suspense abounds, right? Wellllll….

Perhaps much of the problem with how this film was received lies with the audience’s expectations. The Happening was pitched as a return to form for Shyamalan. It was Action Mark Wahlberg in an apocalypse survival movie that the poster claimed was a “nailbitingly ferocious thriller”. This was going to be something we could all get our heads around and enjoy. The trailer was fast-cut, all images of hysterical people fleeing in confusion from an unknown terrorist threat. Marky Mark was gonna save America! Yeah! You wouldn’t be an idiot if you went in expecting a Roland Emmerich style disaster thriller.

What you get, however, is the exact opposite.

Within the first few minutes, Elliott talks to his students about the “interpretation of experimental data”. Shyamalan is giving his audience a clue right here about what they need to do and The Happening is indeed one of the most daringly experimental mainstream films of all time. In some senses, it’s almost an anti-film (and, as a fan of transgressive cinema, I don’t mean this as a snide put-down either).

Just about every aspect of The Happening is a defiance of expectation. It uses the tropes of classic disaster/survival B-Movies (Shyamalan clearly knows his classics) but inverts them. The pacing of the film, for example, moves in reverse. It starts off quite fraught and slows down further and further as it goes on. By the time it reaches its (anti)climax, it’s become almost motionless with fewer words, longer takes, extended periods of stillness and silence; a vastness you can almost feel.

The characters are irregular too. Our hero – traditionally a chiselled macho type, exactly what Wahlberg would normally play – is a science teacher. He speaks in an awkward, squeaky, almost camp voice and makes few actual decisions to drive the action. His character arc pretty much follows the opposite of the classic orphan-wanderer-warrior-martyr structure. He martyrs himself early on by trying to save his wife and his best friend’s daughter, fights a little to get them out of Philadelphia but becomes gradually more lost and orphaned from those around him as the story progresses. Likewise, when they meet the military, they’re (incredibly!) even less assertive; a total opposite of the usual bull-headed hard-asses one finds in disaster films. Private Auster doesn’t even swear, instead exclaiming “Cheese and crackers!” in a ridiculous high-pitched voice when he’s scared.

The dialogue in general becomes weirder when situations show signs of tension. The big showdown scene that’s been building between Elliott and his wife Alma (Zooey Deschanel) is a surreal discussion over an “illicit tiramisu” and a “completely superfluous bottle of cough syrup” that gets deflated before it even has chance to blow up. Whenever Alma references films, she gets them colossally wrong, confusing Fatal Attraction with Psycho and The Exorcist with God-only-knows-what. With this, Shyamalan further distances himself from genre as we know it.

The plotting, likewise, inverts genre convention. Instead of having to reach the city to find denser populations, the survivors must split into smaller and smaller groups, as the toxin affects people when they’re gathered in number. Instead of there being any mystery (or the obligatory “Shyamalan twist!”) we learn within the first act that the toxin making people kill themselves is being generated by the trees; again an interesting take on expectation. There’s one shot near the start in which we see looming nuclear power plants behind a row of green trees. The instinctive reaction is to look at the black smoke and think “well, that’s your evil right there” but instead, it’s the bright and seemingly benign plants in the foreground. The killer is right under your nose from the very start. It’s a non-mystery. A theydunnit.

The title itself is perhaps the most explicit gag of all in relation to these contradictions. It’s called The Happening and yet (as many critics pointed out) almost nothing actually happens throughout the whole film.

But what’s the point? Is it just – as the text suggests – “an act of nature and we’ll never understand it”? Do we simply enjoy the irony and the bizarre humour of wacky dialogue like “Why are you eyeing my lemon drink?” and appreciate it as an almost Zucker Brothers-like spoof of the B-movie? Of course not. Anything that is so lucid and careful in its rejection of the rules must have a reason and The Happening is no exception.

You see, whatever else it may be, the film is undeniably creepy. Even many of its detractors admit that the suicide scenes unnerve them. In my opinion, it’s not so much the visceral elements of these scenes (men running themselves over with lawnmowers, feeding themselves to tigers in the zoo or hanging themselves from trees in groups) that are upsetting. It’s the randomness – the unfathomable juxtaposition of this self-inflicted horror onto normal, everyday life – that’s shocking and therein lies the crux of The Happening.

It taps right into mankind’s fear of chaos. The existential dread that events cannot possibly be connected and that life is both unpredictable meaningless. Before committing suicide, characters become disorientated and repeat things. One of the spookiest scenes in the movie has a young girl telling her mother in monotone, “Calculus, I see in calculus. Calculus. Calculus…” before throwing herself out of the window. This is no throwaway line. The film is rooted in the mathematics of change, humanity’s inability to control it and the emotional agony this causes.

This is why The Happening has to play as an anti-film. To reinforce this abstraction, this inability to connect with the conventions of societal (or in this case cinematic) expectation. It’s a sister piece to Shyamalan’s own Signs, in which everything happened for a reason. Even the most trivial event tied together at the end of Signs to demonstrate the workings of an omnipotent greater force. If Signs was an overtly religious film stating without doubt that there is indeed a God, The Happening is the opposite; a spiritual plea for help – a desperate crisis of faith.

At its heart though, this is a film about suicide. It’s Shyamalan trying to process his horror at the enormity of someone taking their own life. A tortured longing to understand and to soothe the pain of simply living. The text, when you boil it down, is about a man (quite literally) running away from the seemingly inescapable impulse to kill himself. Throughout the film, almost every other character tries to force Elliot to make decisions and take control. They want his help and he can’t even help himself. They scream out for him to bring order into the chaos. The scene in which he yells “Give me a Goddamn second!” and tries to apply science to the situation as half of the party he’s with start to kill themselves is fraught with the pain of a man who can’t cope, who can’t rationally apply order to anything, yet is terrified by the threat of chaos taking control.

In one scene, Elliot seeks shelter in a “model home” where everything (even the wine) is made of plastic. A sign outside states “YOU DESERVE THIS”. The whole world is trying to force order upon Elliot, to make him accept even his own contentment as something he should take charge of, and he can’t face it. In another scene, he sings a jaunty tune in a weird falsetto to prove that he’s “normal” (coming across as anything but). He becomes increasingly abstracted from the world as the film goes on and the pressure increases to take charge of his life. It’s a clear metaphor for the ever-creeping shadow of depression; the frustration of knowing what to do in theory but being unable to bring order to the chaos of the mind. As the film progresses, slowing the pace, paring down the characters, stripping Elliot of almost everyone around him, leaving him no one and nothing to turn to, his surrender to the void seems almost inevitable. Each shot gets wider and lasts longer, expanding to the point where the emptiness is tangible. Tak Fujimoto (of Badlands fame)’s cinematography here is a breathtakingly poignant translation of a director’s very difficult vision.

The final scenes are heartbreaking. Even when I watched them again recently to write this piece, I’m sure I almost forgot to breathe. Elliot and Alma sit in separate houses, communicating through an old talking tube that goes under the ground. It’s symbolic of the separation that the suicidally depressed feel from those who love them; Elliot wants to relate but can’t. The doors aren’t locked, there’s nothing standing between them except the air – the air that, if they go out into it, may cause him to kill himself. The abstract mental chaos that could tip him over the edge. When they take the plunge and walk towards one another to embrace in slow motion, it’s a revelatory, deeply moving moment, as positive a message as one could take from a film so achingly melancholy.

Things work out for them and the “happening” stops as quickly as it started. There is no reason for anything. Sometimes things happen. Sometimes people die. Sometimes they don’t. The world is cruel, unfair, without rules or structure. We can only try our best to survive (which brings us full circle – The Happening is in fact the survival movie we were promised, just deconstructed and reassembled into something entirely new). Yet the very last scene in the film – everything beginning again in Paris – leaves the viewer caught in an existential loop. A disconnection from reality can strike anywhere, to anyone, at any time. Life is precious and all too fragile. A thought as comforting as it is terrifying.

The script here is so carefully constructed, so multi-layered and so rhythmic it’s almost poetry. The fact that much of the dialogue was deemed simply ridiculous by audiences saddens me because every word feels so perfectly in place. The opening line of the film is “I forgot where I am”. Anyone who’s experienced depression need look no further than this beautifully crafted sentence to understand the nature of Shyamalan’s vision here. To create a big budget Hollywood genre film from such a sad place is not commonplace behaviour and for that alone, The Happening should be re-evaluated and appreciated.

It is beautiful, bold, quietly devastating and nothing like any other film ever made. If only every “embarrassing flop” could be so flawless.

Be the first to comment